User:Theleekycauldron/Drafts/Fedorenko v. United States

| Fedorenko v. United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued October 15, 1980 Decided January 21, 1981 | |

| Full case name | Feodor Fedorenko v. United States |

| Citations | 449 U.S. 490 (more) 101 S. Ct. 737; 66 L. Ed. 2d 686 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit |

| Holding | |

| As a person who had assisted the enemy in persecuting civilians, Fedorenko's visa was illegally procured and therefore his citizenship must be revoked under the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

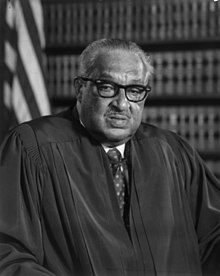

| Majority | Marshall, joined by Brennan, Stewart, Powell, Rehnquist |

| Concurrence | Burger |

| Concurrence | Blackmun |

| Dissent | White |

| Dissent | Stevens |

Fedorenko v. United States, 449 U.S. 490 (1981), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States revolving around the citizenship status of Feodor Fedorenko.

Background[edit]

Case[edit]

The aftermath of World War II saw many attempts on the part of the United States and other Allied countries to address a large number of refugees and other displaced persons stemming from the war. In 1948, the United States government passed the Displaced Persons Act (DPA), which allowed the government to ignore its regular quotas when admitting refugees from the war.[1] However, the act referenced language from the constitution of the International Refugee Organization that excluded the following from being considered "displaced persons":

- War criminals, quislings, and traitors.

- Any other persons who can be shown:

- (a) to have assisted the enemy in persecuting civil populations of countries, Members of the United Nations; or

- (b) to have voluntarily assisted the enemy forces since the outbreak of the second world war in their operations against the United Nations.[2]

One person who came to the United States through the DPA was Feodor Fedorenko, a Ukrainian-born citizen of the Soviet Union. In June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the country as a part of World War II, leading Fedorenko to be drafted into the Red Army. Within a month of being mobilized, he was captured by the Germans. After moving through several prisoner of war (PoW) camps,[3] Fedorenko was trained in early 1942 to be a guard, and was transferred to work at the Treblinka extermination camp in September 1942[4] until an uprising closed the camp in August 1943. He then served as a guard at a PoW camp in Pölitz, and then as a warehouse guard in Hamburg. Before the British entered Hamburg in 1945, Fedorenko left service of the Nazis and did civilian labor work until 1949.[5]

Fedorenko applied for admission to the U.S. through the DPA in 1949, falsely claiming that he was Polish and that he had spent the war working as a farmer there, and then as a factory worker in Pölitz. He claimed that he served in a "labor battalion"; the DPA would have required an investigation to determine whether or not he was a voluntary collaborator with the Nazis, but there is no evidence such an investigation occurred. After six weeks, Fedorenko's application was granted.[5] He lived a quiet life for the next 28 years, working in a factory in Connecticut before retiring to Miami Beach, Florida, in 1976. In 1969, he applied for citizenship, again not disclosing his time at the extermination camp; the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) recommended Fedorenko be naturalized, and in 1970, he was granted U.S. citizenship.[6] Throughout his time in the United States, his only legal infraction was a parking ticket.[7]

Meanwhile, public consciousness was growing aware of Nazis and collaborators living quietly in the United States, with high-profile cases such as Hermine Braunsteiner coming to light in the 1960s and '70s. Two U.S. Representatives, Joshua Eilberg and Elizabeth Holtzman, began calling attention to the issue in order to urge the government to root out domestic war criminals.[8] As early as 1964,[9] Fedorenko's name was on a list of 59 suspected war criminals compiled by one Dr. Otto Karbach, who had been collecting Yiddish-language newspaper clippings of Holocaust survivor testimonials over the years. In 1973, he gave the list to the INS; this, as well as pressure from Eilberg and Holtzman, led the INS to create an "office" to investigate the charges. The office comprised of exactly one man, Sam Zutty, a career INS investigator.[10] He worked with Israeli police to find survivors who could identify the people in question; this led to mixed results. One 76-year survivor named Eugen Turkowski insisted that one a man in a spread of photographs was Fedorenko, when it was actually John Demjanjuk.[11] Zutty's office proved on the whole to be largely ineffective, filing no cases for the first three years the task force existed.[12] In response to a January 1977 letter from Holtzman's subcommittee, the Government Accountability Office found that while there was no conspiracy to protect Nazis from investigation, the INS had proved incompetent to investigate the allegations before it.[13]

Finally looking to alleviate pressure, the government[a] brought denaturalization proceedings against Fedorenko and nine other suspected war criminals from late 1976 through 1977. The government, however, proved to be wholly unprepared for trial; it had located no domestic witnesses, had not prepared the witnesses it did have for trial, did not interview its elderly witnesses (instead hoping that they would survive long enough to take the stand in court), and was not familiar with court standards for photographic identification. Days before the commissioner of the INS was set to testify before Eilberg's subcommittee in July 1977, Zutty's office was dissolved and replaced with a special litigation unit.[17] The special litigation unit brought no new cases, but the government proceeded with five of these cases post-reorganization, and Fedorenko's case went to trial.[18]

Denaturalization[edit]

In Article I of the U.S. Constitution, the federal government is given the power "to establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization".[19] As a part of this power, Congress passed the Naturalization Act of 1906, which provided that a person could be denaturalized in cases of fraud or where the citizenship was "illegally procured".[20] The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of that act as a part of its ruling in Johannssen v. United States (1912). In 1952, Congress overwrote that statute with one providing for reversing citizenship obtained "by concealment of a material fact or by willful misrepresentation", adding the illegal procurement language back in 1961.[21]

Materiality proved to be a controversial issue among courts, which could not agree as to what constituted a material fact. While the Supreme Court ruled in Johannssen that a fact that would have been disqualifying if disclosed should be considered material, less obvious cases provoked disagreement. Some courts thought that merely stymying an investigation that could have turned up more relevant evidence would be enough to revoke citizenship. Courts struggled with similar problems in deportation cases, developing other standards in that arena. Often, courts would lump various denaturalization criteria together or reference them vaguely.[22]

The Supreme Court attempted to clarify the standard of materiality in Chaunt v. United States (1960), providing for a two-pronged test where satisfying either would demonstrate materiality. The first prong affirmed the widely agreed-upon standard, while the second designated facts material where the "disclosure might have been useful in an investigation possibly leading to the discovery of other facts warranting denial of citizenship". This second prong seemingly struck a balance between prior approaches by lower courts; an investigation was necessary to satisfy it, but not sufficient.[23]

Chaunt failed to reduce the confusion and disarray of lower court decisions on the subject, even leading to a circuit split between the Ninth and Second Circuit Court of Appeals. In United States v. Rossi (1962) and La Madrid-Peraza v. INS (1974), the Ninth Circuit held that the second prong of Chaunt still required the government to show that the facts discovered on a potential investigation would have caused the denial of citizenship. Rossi was also one case that extended the definition of materiality to visa applications, not just citizenship cases, as courts did consistently at the time. The Second Circuit ruled differently in United States v. Oddo (1963), arguing that the second prong only required the government to show that a potential investigation could conceivably have turned up more relevant information.[24]

Equity[edit]

Rather than being suits in common law, civil denaturalization cases are decided in equity.[b] This holding dates back to the District Court for the Southern District of New York's ruling in Mansour v. United States (1908), denying the defendant's request for a jury. The court ruled that denaturalization cases are analogous to suits to cancel a government-given grant or patent, which are treated as suits in equity, and that denaturalization cases should be decided similarly.[25] The Supreme Court agreed with this reasoning in Luria v. United States (1913), although it did not cite Mansour. At the time Fedorenko was decided, Luria was not seriously challenged as settled precedent.[26] Despite the proceedings being designated as equitable, the Supreme Court has made past rulings that narrow the set of rights normally available to defendants in equitable proceedings. In some of its early decisions, the Supreme Court ordered denaturalization for minor errors such as not making sure that a certificate of lawful arrival was attached to the application for citizenship or not holding the final hearing in open court, holding that it was the responsibility of the applicant to meet all requirements for citizenship and that the law leaves no room for equitable discretion in that matter.[27]

However, the Court has also ruled that naturalized citizens enjoy all of the same rights and privileges as citizens by birth.[28] The courts' pattern of ordering denaturalization liberally changed somewhat in Schneiderman v. United States (1943), in which the Court ruled that it was the government's responsibility to provide "clear, unequivocal, and convincing" evidence in favor of denaturalization, a high bar that approached the "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard of criminal law.[27][29]

Lower courts[edit]

District court[edit]

Trial[edit]

The United States brought civil denaturalization proceedings against Fedorenko in 1977.

The trial was a civil proceeding,

The government was represented by four lawyers, led by the chief assistant U.S. district attorney, John Sale. Fedorenko was represented by Gregg Pomeroy, a lawyer who had served in the local public defender's office but was in private practice by then.[7]

Admitted into evidence was Fedorenko's original 1949 visa application, which contained a photo of him from the time. This made the witnesses' task of identifying the defendant easier, but the trial .

The government called six survivors of Treblinka to the witness stand, all of Israeli citizenship.[30] Their names were Eugun Turkowski, Shalom Kohn, Josef Czarny, Gustaw Boraks, Sonia Lewkowicz, and Pincas Epstein. All six, with the exception of Czarny, said that they had seen Fedorenko beat, whip, or shoot Jews during their time in Treblinka and recounted those stories; Kohn claimed that Fedorenko beat him personally. Czarny presented more circumstantial evidence, but admitted on cross-examination that he had not specifically seen Fedorenko commit the acts he was detailing. Identification of Fedorenko was somewhat trickier: when asked to point to a man in the room, Turkowski incorrectly identified an elderly man in the spectators' section. The courtroom identification was not strictly necessary; Fedorenko's initial application had been admitted into evidence, and the witness correctly identified Fedorenko in the photograph. However, it did damage the government's case. Kohn correctly identified Fedorenko in the room; Czarny, Boraks, and Epstein had correctly identified an earlier picture of Fedorenko from a photo spread shown to him in Israel. On cross-examination of Turkowski and Kohn, Gregg Pomeroy emphasized the involuntary nature of the work they had done at Treblinka, looking to bolster their own argument that Fedorenko had committed those actions under duress.[31]

- fact check witness identification in np.com

The first witness was 64-year-old Eugun Turkowski, who survived on account of being a mechanic the Germans could put to use. He testified through a Hebrew language–interpreter that he knew Fedorenko because he would come into the repair shop where Turkowski worked, and that he had seen Fedorenko beat and shoot Jews and sometimes order around other guards. [32]

Ruling[edit]

The district court ruled for Fedorenko, rejecting the testimony of the Treblinka survivors and Jenkins. Roettger found the photographic spread to constitutionally invalid for identification, as the photograph containing Fedorenko was clearer and bigger than its neighbors, and the spread contained as few as three photos for some of the witnesses. The in-court identification was also ruled invalid, as the court speculated that the two witnesses who correctly pointed out Fedorenko may have been coached following Turkowski's gaffe. The court, therefore, found that the witnesses' testimony was mostly not credible, and the government had not satisfactorily proved that Fedorenko had willingly committed any atrocities that would disqualify him.[33]

On Jenkins' testimony and the question of materiality, the court rejected the government's argument for a broad interpretation of Chaunt, instead ruling that its second prong only applied where the investigation in question would have revealed disqualifying facts. Roediger reasoned, relying on the Ninth Circuit, that an investigation at the time would have found that Fedorenko was forced to work as a guard at Treblinka and would have admitted him.[34][35] Fedorenko might have been disqualified on the plain language of the DPA – the disqualifying clause, section 2(a), does not explicitly contain an exemption for duress, while section 2(b) does – but the court ruled that if the persecution clause did not have a duress exemption, it would be forced to deny entry to kapos, an unjust result that necessitated the existence of a voluntariness standard.[36] Finally, the court asserted that it had discretion as a court in equity to rule for Fedorenko, given his nearly three decades living in the United States with a near-spotless record in that time. Citing the evidence presented in support of Fedorenko's character, including being viewed positively by people around him, Roettger found that his power to make sure the case had a fair outcome – regardless of the law – extended to ruling to preserve his citizenship.[37]

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals[edit]

Following the embarrassing performance in this case and others, the special litigation unit was reorganized into the Office of Special Investigations (OSI) under the Department of Justice, which greatly expanded its budget and capabilities.[38] Under OSI management,[16] The government appealed the district court's ruling to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, disputing the decision with respect to materiality, equitable discretion, and reliability of witness testimony. On June 28, 1979, writing for a three-judge panel, John Minor Wisdom reversed the district court's ruling on the first two grounds. The third was ignored, as the first two were deemed sufficient to reverse. With regards to materiality, the Fifth Circuit followed the Second Circuit's path in the split on Chaunt, ruling that since a disclosure might have caused the government to find facts worth denying citizenship, the misrepresentation was material. The court reasoned that following the Ninth Circuit would require the government to investigate and conclusively discover disqualifying facts, and then prove them against a high standard of evidence. Such a barrier would be too difficult for the government to meet, the court reasoned, and would instead incentivize applicants to misrepresent their cases.[35]

The appeals court also ruled that the district court erred in using equitable discretion to justify ruling for Fedorenko, holding that it had no discretion to apply to the instant case:

There is a crucial distinction between a district court's authority to grant citizenship and its authority to revoke citizenship. In the former situation, the court must consider facts and circumstances relevant to determining whether an individual meets such requirements for naturalization as good moral character and an understanding of the English language, basic American history, and civics. The district courts must be accorded some discretion to make these determinations. Once it has been determined that a person does not qualify for citizenship, however, the district court as no discretion to ignore the defect and grant citizenship. The denaturalization statute does not accord the district courts any authority to excuse the fraudulent procurement of citizenship.[39]

The appeals court ordered that Fedorenko's citizenship be revoked. The Supreme Court granted a writ of certiorari to consider whether Fedorenko's citizenship was cancellable on statutory grounds, and whether equitable discretion could counteract that.[40] Benjamin Civiletti argued the government's case before the Court, his only oral argument delivered while serving as the Attorney General.[16]

Supreme Court[edit]

Writing for the majority on January 21, 1981,[41] Justice Thurgood Marshall affirmed the appeals court's judgment, but not its rationale.[42] The Court distinguished Chaunt from automatic application to this case, as that case concerned misrepresentations on a citizenship application about events occurring after the visa was granted. This case, on the other hand, concerned misrepresentations made on the visa application about events occurring prior to entry. The Court determined that it would be appropriate to decide whether the misrepresentation test created in Chaunt applied to visa applications, but then dismissed the question as pragmatically unnecessary by negating Fedorenko's procurement of his visa.[43]

In defining a new minimum standard of materiality for visa applications, the Court held that "at the very least, a misrepresentation must be considered material if disclosure of the true facts would have made the applicant ineligible for a visa." It then held that under the plain language of the act and Jenkins' testimony, Fedorenko was ineligible for his visa, rejecting the district court's interpretation of the voluntariness standards in the DPA. Because section 2(a) did not contain an exemption for duress, while section 2(b) did, the Court held that it did not have to consider duress in its construction of 2(a).[44] The Court ruled that Fedorenko's involvement under the act was enough to be disqualified under 2(a), whereas a Jewish inmate forced to cut the hair of other inmates in preparation for execution would not qualify. It deferred the question of kapos to a future case.[45] Despite the district court's finding that Fedorenko's service was not voluntary, he was ineligible for his visa at the time he applied, and thus his misrepresentation was material.[46]

From there, the Court concluded that Fedorenko's citizenship must be revoked as well; the DPA required that persons admitted under the act comply with all immigration laws in force. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 provided that applicants for citizenship needed to have been approved for permanent residence, which is impossible without a valid visa. Since Fedorenko's visa was invalid, his citizenship was deemed "illegally procured" and thus revocable.[47] On the issue of equitable discretion, the Court affirmed the appeals court's decision, holding that while equity can be used to emphasize or deemphasize facts in a naturalization case, the district court judge had no power to use equity in determining the result of a denaturalization case.[48] Chief Justice Warren E. Burger concurred in the judgement, but did not file an opinion.[49]

Other opinions[edit]

Justice Harry Blackmun concurred, but held that majority should have applied Chaunt to the instant case because he felt that the facts used to distinguish Chaunt were immaterial. He reasoned that had it Chaunt been applied, its first prong would have had the same effect of disqualifying Fedorenko based on the testimony of Jenkins; the facts, if discovered, would have led to denial of a visa. He also noted that lower courts had been applying Chaunt consistently to visa applications. On the second prong of Chaunt, Blackmun defended the district court's view that the misrepresented facts would have to lead to the discovery of disqualifying truths to be material. He argued that if every misrepresentation was subject to scrutiny on the basis that it might have led to the discovery of disqualifying facts, then naturalized citizenship was made too vulnerable and easily revoked when it should be equal to that of a natural-born citizen.[50]

Justice John Paul Stevens dissented, writing that the Court acted on a "theory that no litigant argued, that the Government expressly disavowed".[51] Regarding the DPA, Stevens agreed with the district court's rejection of the voluntariness distinction between 2(a) and 2(b). He contended that despite 2(a) containing a duress exception and 2(b) not, 2(a) certainly had to incorporate a distinction of duress regardless; otherwise, it would disqualify Jewish kapos, a result he felt was unacceptable.[52] On the issue of Chaunt, he echoed the view that the government should have to prove that a misrepresentation stymied discovery of disqualifying facts to show materiality. He concluded that what he saw as the Court's error would cause "human suffering".[53]

Justice Byron White also dissented, arguing that rather than relying on the DPA, the Court should have clarified the Chaunt standard and remanded the case to the appeals court to review the district court's findings. He agreed with the majority's ambivalence on whether or not to apply Chaunt to visa applications,[54] but also noted that the appeals court failed to review the district court's use of Chaunt on Fedorenko's citizenship application.[55] White agreed with the appeals court's interpretation of Chaunt more than the district court's, but disagreed with the Supreme Court's interpretation of the DPA; he argued that a voluntariness standard might well be contained in the use of the words "assist" and "persecute" in the DPA, which would influence the outcome of the case.[56]

Aftermath[edit]

- Wunsch criticizes equitable discretion

- Dienstag on duress

Following the Supreme Court's ruling, Fedorenko was subject to deportation proceedings. The Board of Immigration Appeals refused to make a duress exemption for him, and thus Fedorenko was ordered to leave the country. In December 1984, after being refused by Canada, Fedorenko was deported to the Soviet Union. In 1986, he pled guilty to all charges of treason and war crimes and was sentenced to death. On July 28, 1987, the Soviet Union announced that they had executed him.[57]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Exactly who handled and initiated Fedorenko's prosecution in the district court is disputed. Some claim that it was initiated by Zutty's office and transferred to the special litigation unit;[14] others claim that the INS gave the case to the Department of Justice;[15] still others claim that the special litigation unit's involvement was limited at best, but that it still received most of the blame for the case's early results.[16]

- ^ The U.S. government can also seek denaturalization through an indictment in criminal court, under 18 U.S.C § 1425. See Maslenjak v. United States, 582 U.S. ___.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Bylciw 1982, p. 951.

- ^ Dienstag 1982, pp. 124, fn. 16. Quoting IRO Constitution.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, p. 251.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, p. 252.

- ^ a b Parker 1982, p. 411.

- ^ Rinaldi 1979, p. 299; Parker 1982, p. 411.

- ^ a b Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, p. 253.

- ^ Douglas 2016, pp. 32–33; Ryan 1984, p. 51–52.

- ^ Rinaldi 1979, p. 299.

- ^ Ryan 1984, p. 52; Douglas 2016, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Douglas 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Ryan 1984, p. 55.

- ^ Douglas 2016, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Ryan 1984, p. 60.

- ^ Rinaldi 1979, p. 300.

- ^ a b c Douglas 2016, p. 49.

- ^ Ryan 1984, p. 59.

- ^ Ryan 1984, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Binder 1982, p. 134. Quoting U.S. Constitution, article I, section 8, clause 4.

- ^ Binder 1982, p. 134, explicitly refers to the act as the "Immigration and Nationality Act of 1906", but no act exists by that title and the language used by Binder matches the text of the Naturalization Act of 1906. Quoting Naturalization Act of 1906.

- ^ Binder 1982, pp. 134–135. Quoting Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952.

- ^ Binder 1982, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Binder 1982, p. 136–137. Quoting Chaunt v. United States, 364 U.S. at 355.

- ^ Binder 1982, p. 137; Parker 1982, pp. 415, 418.

- ^ Wunsch 1981–1982, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Wunsch 1981–1982, pp. 364–365.

- ^ a b Binder 1982, p. 135.

- ^ Wunsch 1981–1982, p. 363.

- ^ Wunsch 1981–1982, p. 366.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, p. 254.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014. Turkowski on pp. 254–256; Kohn on pp. 256–257; Czarny on pp. 257–258; Boraks on pp. 258–259; Lewkowicz on p. 261; Epstein on pp. 261–262.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Parker 1982, pp. 413–414; Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, p. 266.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, pp. 267–268; Parker 1982, p. 416.

- ^ a b Parker 1982, pp. 417–419.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, pp. 268–269.

- ^ Ryan 1984, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Evans 1980, pp. 188–189. Quoting United States v. Fedorenko, 597 F.2d at 953–954.

- ^ Binder 1982, pp. 129, 132.

- ^ Wunsch 1981–1982, p. 360.

- ^ Bylciw 1982, p. 957.

- ^ Bylciw 1982, p. 958–960.

- ^ Tuggle 1981, p. 369; Bylciw 1982, p. 960. Quoting Fedorenko v. United States, 449 U.S. at 509.

- ^ Bazyler & Tuerkheimer 2014, p. 270.

- ^ Tuggle 1981, p. 369; Bylciw 1982, p. 960.

- ^ Binder 1982, p. 134.

- ^ Bylciw 1982, pp. 961–962.

- ^ Parker 1982, p. fn. 4.

- ^ Parker 1982, p. 420–421.

- ^ Parker 1982, p. 422.

- ^ Bylciw 1982, p. 965.

- ^ Bylciw 1982, p. 966.

- ^ Bylciw 1982, pp. 963–964.

- ^ Tuggle 1981, p. 370.

- ^ Parker 1982, pp. 421–422; Bylciw 1982, pp. 963–964, fn. 96; Tuggle 1981, p. 370.

- ^ Schmemann 1986; Barringer 1987; Getschman 1988, pp. 310–311.

Works cited[edit]

Academic sources[edit]

- Rinaldi, Matthew (1979). "The disturbing case of Feodor Fedorenko". Judaism. 28 (3): 293–303. ProQuest 1304359146.

- Evans, Alona E. (1980). "Citizenship—denaturalization—failure to disclose service as concentration camp guard during Second World War". American Journal of International Law. 74 (1): 186–189. doi:10.2307/2200914.

- Tuggle, Bernie M. (1981). "Fedorenko v. United States: The memories and emotions of World War II endure". Denver Journal of International Law & Policy. 10 (2): 367–373.

- Wunsch, Gerald A. (1981–1982). "Should equitable discretion apply in denaturalization proceedings: Fedorenko v. United States". Immigration and Nationality Law Review. 5: 359–378.

- Binder, Patricia A. (1982). "Fedorenko v. United States: A new test for misrepresentation in visa applications". North Carolina Journal of International Law. 7: 129–141. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- Bylciw, Diane Goffer (1982). "Immigration law--revocation of citizenship--Fedorenko v. United States". New York Law School Law Review. 27 (3): 951–970.

- Dienstag, Abbe L. (1982). "Fedorenko v. United States: War crimes, the defense of duress, and American nationality law". Columbia Law Review. 82 (1): 120–183. doi:10.2307/1122241. JSTOR 1122241.

- Parker, Jann M. (1982). "Establishing workable standards in denaturalization proceedings: Fedorenko v. United States". Connecticut Law Review. 14 (2): 409–434.

- Ryan, Allan A. (1984). Quiet Neighbors: Prosecuting Nazi War Criminals in America. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- Getschman, Gregory J. (1988). "The uncertain role of innocence in United States efforts to deport Nazi war criminals". Cornell International Law Journal. 21 (2): 287–316.

- Bazyler, Michael J.; Tuerkheimer, Frank M. (2014). "The trial of Feodor Fedorenko: Treblinka relived in a Florida courtroom". Forgotten Trials of the Holocaust. New York University Press. pp. 247–273. ISBN 9781479899241. JSTOR j.ctt9qfr64.13.

- Douglas, Lawrence (2016). The Right Wrong Man: John Demjanjuk and the Last Great Nazi War Crimes Trial. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400873159.

Legal citations[edit]

- Naturalization Act of 1906, Pub. L. 59–338, 34 Stat. 596.

- Displaced Persons Act (1948), Pub. L. 80-744, 62 Stat. 1009.

- IRO Constitution, Annex I Pt. II, 62 Stat. 3051, 18 U.N.T.S. at 20.

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, Pub. L. 83-414, 66 Stat. 261.

- Chaunt v. United States, 364 U.S. 350 (1960).

- United States v. Fedorenko, 597 F.2d 496 (1979).

- Fedorenko v. United States, 449 U.S. 490 (1981).

Other sources[edit]

- Schmemann, Serge (June 20, 1986). "Soviet dooms war criminal who was deported by the U.S." The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- Barringer, Felicity (July 28, 1987). "Soviet reports it executed Nazi guard U.S. extradited". The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

See also[edit]

- Chaunt v. United States, 364 U.S. 350 (1960)

- Rogers v. Bellei, 401 U.S. 815 (1971)

- Kungys v. United States, 485 U.S. 759 (1988)

- Negusie v. Holder, 555 U.S. 511 (2009)

- Boļeslavs Maikovskis, Latvian Nazi collaborator, fled the U.S. before his extradition

- Anton Geiser, who lost his U.S. citizenship for similar reasons, this case having played an important part in the process

- Treblinka trials

External links[edit]

- Text of Fedorenko v. United States, 449 U.S. 490 (1981) is available from: Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)

Category:United States immigration and naturalization case law Category:United States Supreme Court cases Category:United States Supreme Court cases of the Burger Court Category:1981 in United States case law Category:Nazism Category:Denaturalization case law