User:HistoryofIran/Treaty of Gulistan

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user in whose space this page is located may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:HistoryofIran/Treaty_of_Gulistan. |

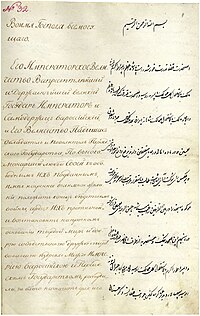

First page of the Treaty of Gulistan | |

| Signed | 24 October 1813 |

|---|---|

| Location | Gulistan |

| Signatories | |

| Languages | |

The Treaty of Gulistan (Persian: عهدنامهٔ گلستان; Russian: Гюлистанский договор) was signed between Qajar Iran and the Russian Empire on 24 October 1813, thus concluding the Russo-Iranian War of 1804–1813.

Background[edit]

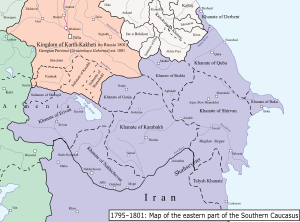

Fath-Ali Shah Qajar (r. 1797–1834), the second shah (king) of Iran's newly found Qajar dynasty, was embroiled in a conflict with Russia over the Caucasus as soon as he came to power in 1797. After many years of being subject to Iranian rule, the Christian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti (located in Eastern Georgia) decided to reject their rule. It made the decision to look to Russia for defense against Iran after rejecting rule by the Qajars. Since the previous shah Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar (r. 1789–1797) had been slain in the Caucasus during a military campaign, this was an important matter for the Qajar dynasty.[1]

The reign of the Russian tsar (emperor) Alexander I (r. 1801–1825) saw an increased desire on the part of the Russians to increase their presence and influence in the Caucasus, where they had already shown interest since the 1760s. Prince Pavel Tsitsianov, who Alexander I appointed to oversee Caucasian affairs in 1803, had nothing against about using violence, but any infringement of Iran's control over the Caucasus was not something that the Qajar administration could just ignore. Since 1502, Iran had controlled the Caucasus and the Iranians saw it as a natural extension of their country.[1]

In mid-January 1804, Tsitsianov invaded Ganja and conquered its fortress; its governor, Javad Khan, was killed, and between 1,500–3,000 residents were slaughtered.[1][2] Russian law replaced Islamic law, and the congregational mosque was transformed into a church. This marked the beginning of the first Russo-Iranian War. On May 23, 1804, Fath-Ali Shah ordered Russian forces to depart from Iranian territories in the Caucasus. Iran interpreted their unwillingness to comply with this as an act of war.[1]

Negotations[edit]

Treaty content and signing[edit]

Right: Mirza Abolhassan Khan Ilchi, who signed the treaty behalf of Iran

Due to British pressure and promises, actual financial difficulties, and military difficulties elsewhere, Fath-Ali Shah ultimately conceded defeat to the Russians. On the recommendation of the chief minister Mirza Shafi Mazandarani and others, he grudgingly agreed to this arrangement in the hopes that the British, acting as the Russian emperor's intermediary, could secure a more favorable agreement for him. One observer hypothesized that Fath-Ali Shah's acceptance of peace with Russia was due to Iranian political officials' little knowledge of the world's affairs and their reliance on Ouseley's pledge to advocate for the return of some of the territories under Russian occupation. It was well known that Mirza Shafi, who favored peace with the Russians, knew more about European politics than other politicians in Tehran. He had already come to the conclusion that the war with Russia was unwinnable, therefore he may have tried to stop additional land loss by convincing Fath-Ali Shah to make peace with Russia. Numerous domestic uprisings as well as economic issues were taking place in Iran.[3]

Mirza Abolhassan was chosen by Mirza Shafi Mazandarani to be the only representative of Iran, since Abbas Mirza and Mirza Bozorg refused to ratify any agreement that called for the loss of Iranian territory. On October 2, 1813, with a retinue of 350 people, Mirza Abolhassan departed the city of Tabriz and by October 9 he was at the Golestan village in northern Karabakh, which had been chosen the last negotiation location. He was greeted by the Russian general and negotiator Nikolay Rtishchev, who had been accompanied by a full retinue of soldiers and had been at the village since October 5. Bournoutian states that; "It is clear that Ouseley had decided to cooperate fully with Russia and abandon Iran to its fate. In fact, on October 12, Rtishchev sent a letter to Ouseley in which he thanked the latter for his great services to Russia in these negotiations"[4]

Mirza Abolhassan gave Rtishchev a note by Ouseley, which he requested to be inserted in the draft of the treaty. The note asked for permission for Iran to send an ambassador to Russia in order to ask for the return of their lost lands.[5] As he waited for a reply, Mirza Abolhassan asked Rtishchev whether Russia could give Iran a very little piece of land as an act of goodwill. Rtishchev accepted, thus giving Iran back the town of Meghri, which the Russian army had already withdrawn from. On October 24, Mirza Abolhassan and Rtishchev signed the Treaty of Golestan, on behalf of Iran and Russia, respectively.[6]

Rtishchev inserted Ouseley's note in the margin of the treaty after it was signed, and thus it did not appear in any of the treaty's articles. The Iranian historian Mirza Fazlollah Khavari Shirazi reported that Rtishchev ordered Georgian and Armenian scribes who were proficient in Persian to record the treaty's Persian translation since he would not allow Agha Mirza Mohammad Na'ini to write the treaty's text in that language. The treaty was officially confirmed on 15 September 1814 in Tiflis.[6] Per the terms of the treaty, Iran conceded to Russia the sultanates of Shamshadil, Qazzaq, Shuragol, and the khanates of Baku, Derbent, Ganja, Shakki, Quba, Shirvan, Karabakh, and the northern and central part of Talish.[7][6] Moreover, Iran also had to abandon its claims over Georgia.[8]

The Treaty of Golestan's territorial arrangements were unclear, for example, in Talish, where it was left up to the mutually appointed administrators to "determine what mountains, rivers, lakes, villages, and fields shall mark the line of frontier." If one of the participants to the treaty felt that the other party had "infringed on" territorial possessions claimed in accordance with the status quo principle, even the limits laid forth in the treaty could be changed. This essentially ensured that territorial conflicts would persist after the treaty's authorization. The region between Lake Gokcha and the city of Erivan remained one of the most disputable, and the Russian military's takeover of the Gokcha district in 1825 served as the catalyst for the second Russo-Iranian War, which lasted from 1826 to 1828.[2]

Reactions[edit]

The Treaty of Gulistan was strongly opposed by officials like Mirza Bozorg Qa'em-Maqam and was a huge disappointment to the Iranians. The Qajars found it extremely difficult to deal with these losses, due to the religious zeal they had sparked by inciting the Shia clergy to proclaim the conflict with Russia to be a holy war, as well as failing to get an accurate depiction of the strength of the Russian army when it was not embroiled in a larger European conflict. Tension arose between Iran and Britain due to to the unsatisfying terms of the treaty, Ouseley not convincing the tsar to reduce the territorial requirements as he had promised, and ongoing disagreements over the British government's inconsistent pledges to provide assistance and payments to Iran.[2]

While not entirely fulfilling the Russians' territorial goals—notably those of their governors and military officers in the Caucasus—the treaty did, nonetheless, significantly expand Russia's participation in Iran's political and economic aspects.[2]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Pourjavady 2023.

- ^ a b c d Daniel 2001, pp. 86–90.

- ^ Behrooz 2023, p. 101.

- ^ Bournoutian 2021, p. 232.

- ^ Bournoutian 2021, pp. 231–233.

- ^ a b c Bournoutian 2021, p. 233.

- ^ Behrooz 2023, p. 102.

- ^ Bournoutian 1992, p. 21.

Sources[edit]

- Amanat, Abbas (2017). Iran: A Modern History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300112542.

- Behrooz, Maziar (2023). Iran at War: Interactions with the Modern World and the Struggle with Imperial Russia. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0755637379.

- Bournoutian, George (1992). The Khanate of Erevan Under Qajar Rule: 1795–1828. Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-0939214181.

- Bournoutian, George (2016). "Prelude to War: The Russian Siege and Storming of the Fortress of Ganjeh, 1803–4". Iranian Studies. 50 (1). Taylor & Francis: 107–124. doi:10.1080/00210862.2016.1159779. S2CID 163302882.

- Bournoutian, George (2021). From the Kur to the Aras: A Military History of Russia's Move into the South Caucasus and the First Russo-Iranian War, 1801–1813. Brill. ISBN 978-9004445154.

- Daniel, Elton L. (2001). "Golestān Treaty". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume XI/1: Giōni–Golšani. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 86–90. ISBN 978-0-933273-60-3.

- Javadi, H. (1983). "Abu'l-Ḥasan Khan Īḷčī". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume I/3: Ablution, Islamic–Abū Manṣūr Heravı̄. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 308–310. ISBN 978-0-71009-092-8.

- Kashani-Sabet, Firoozeh (2014). Frontier Fictions: Shaping the Iranian Nation, 1804–1946. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1850432708.

- Kazemzadeh, F. (1991). "Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin R. G.; Melville, Charles Peter (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 7: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 314–350. ISBN 0-521-20095-4.

- Pourjavady, Reza (2023). "Russo-Iranian wars 1804-13 and 1826-8". Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 20. Iran, Afghanistan and the Caucasus (1800-1914). Brill.